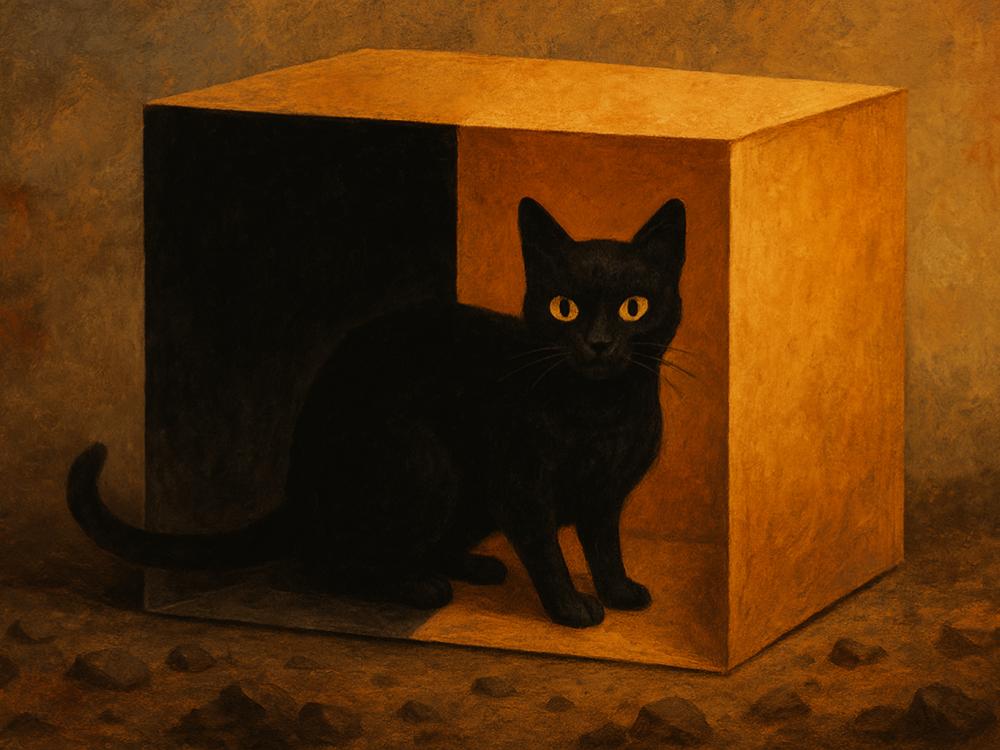

Schrödinger's Cat Goes Beyond Physical Observation.

The famous cat was never meant to frighten anyone; it was meant to make a point about how our descriptions of the world can outgrow the cages we build for them. In the usual telling, a sealed box carries a small quantum drama in which a radioactive decay may trigger a poison vial and turn a living animal into an unsettling superposition of alive and not alive, a thought experiment that forces us to consider what counts as a measurement and when facts become facts. That scene is vivid enough to live in textbooks, yet its reach extends well beyond the physics lab, because the box quietly asks how knowledge forms, whose perspective turns uncertainty into decision, and what responsibilities follow once we admit that observation is never only a matter of eyes and instruments but also of agreements, narratives, and stakes.

What the Box Actually Holds

In the technical story, a quantum system evolves according to smooth, unitary rules until an interaction that qualifies as a measurement produces a result; the cat dramatizes the gap between a microscopic rule set that tolerates superposition and a macroscopic world that does not. Physicists have offered many accounts of how the gap closes, from collapse postulates that treat measurement as a special event, to Everett's branching picture in which outcomes proliferate, to decoherence accounts that explain how environmental interaction suppresses interference and leaves us with stable records. Each story aims to protect the integrity of predictions while explaining why we observe definite cats rather than spectral averages. The box, however, keeps demanding more, because the experiment is not only about how a wave function behaves; it is about how communities decide when the behavior has been recorded and what counts as a reliable trace of reality.

Measurement as a Social Practice

Open any serious experiment log and you will not find magic in the margins; you will find calibration schedules, inter-lab comparisons, error models, and a running conversation about thresholds for calling something a detection. The cat becomes a parable for this larger process, suggesting that observation is at least two things at once: a physical coupling that leaves a mark in the world, and a social ritual that teaches many minds to read the mark the same way. Whether one prefers collapse, many worlds, or decoherence, the decisive moment in practice is the creation of a record that survives scrutiny. A Geiger counter that clicks, a photographic plate that darkens, a qubit register that prints a bit string, all of these are physical events and also invitations to consensus, and the invitation must be answered by procedures strict enough that strangers can agree on what happened.

The Cat and the Scope of Knowledge

The image of a sealed box tempts us to think that knowledge begins only when the lid lifts, yet most of what matters in science happens before anyone peeks: the careful design of the apparatus, the clarity of operational definitions, the prior decision about what will count as "alive" and "not alive," and the chain of validations that let one apparatus stand in for another across time and place. In that sense the cat teaches that observation is not a single flash of insight but a corridor of work that extends from theoretical modeling to engineering tolerances to the language in which the result is reported. The corridor matters because it reveals a quiet truth about knowledge, namely that facts are not found like coins under a cushion; they are prepared, elicited, and stabilized through methods that make them durable enough to travel.

Beyond Physics: Decision Under Uncertainty

Once the lesson is framed this way, it migrates easily into the domains we move through every day. In medicine, a diagnosis oscillates in the file until sufficient tests, thresholds, and second opinions settle it, and the settlement is both a physical story about biomarkers and a social story about protocols and consent. In finance, a model projects a distribution of outcomes that may carry real assets into something like a superposition of viable and insolvent until a reporting date or a market event collapses the range and sets a price, again through rules that combine recorded events with negotiated interpretation. In public policy, evidence accumulates through studies that must be designed, replicated, and reviewed before a decision can be justified as knowledge rather than preference. The cat, in these halls, is a reminder that uncertainty is not an embarrassment to be concealed; it is a condition to be managed with procedures that earn trust.

The Observer Is Not a Single Person

Another extension of the metaphor appears in the discussions that follow Wigner's question about a friend who performs a measurement inside the box while an outside observer treats the entire room as a quantum system. The puzzle dramatizes the way perspective can shift what counts as a settled event, yet outside of the seminar room the practical answer is almost always institutional rather than metaphysical. We build layers of observation, from instruments to operators to auditors, in order to prevent any one vantage from deciding too much, and the layering converts the fragile moment of an individual reading into a robust network of checks. The cat is not waiting for a single gaze; it is waiting for a process that renders private impressions into public facts.

Information, Memory, and Meaning

However one interprets quantum mechanics, observation produces records, and records are a form of memory that must resist noise long enough to guide action. The vial that shattered or did not, the counter that clicked, the timestamp written to storage, these are physical changes and also the beginning of meaning, because meaning is what we call a record once it is placed inside a narrative that tells us how to respond. The cat reminds us that meaning does not float free of material traces, yet it also reminds us that the traces alone do not decide; people decide, after training and debate, how to treat the traces as evidence. When those decisions are careful, the world answers with stability. When they are sloppy, the world answers with error.

The Ethical Edge of Opening the Box

Thought experiments are safe because nothing breathes in them, but the metaphor we inherited carries a living creature, and that detail matters when we lift it out of physics into the larger world. Many of our boxes hold people: clinical trials that must balance risk and benefit, classrooms where assessments can collapse complex lives into binary judgments, algorithms that produce classifications with real consequences. To say that observation goes beyond physical coupling is to accept that the design of the box is an ethical act, that thresholds and labels have human costs, and that the duty of an observer is not only to record accurately but to justify the frame inside which recording occurs.

The Cat We Keep

In the end the cat survives as a traveling lesson about how reality meets our methods and how our methods meet each other. The physics remains extraordinary, and the debates about collapse, branches, and decoherence continue to refine our picture of nature, but the deeper gift of the box is a habit of mind. Build apparatus that couples cleanly to the world, build communities that read the traces with shared discipline, and build narratives that state both what the record shows and what it cannot yet decide. When those habits hold, the lid can lift without drama, because the work that makes observation meaningful has already been done.